©

afrocubanas.com

©

afrocubanas.com

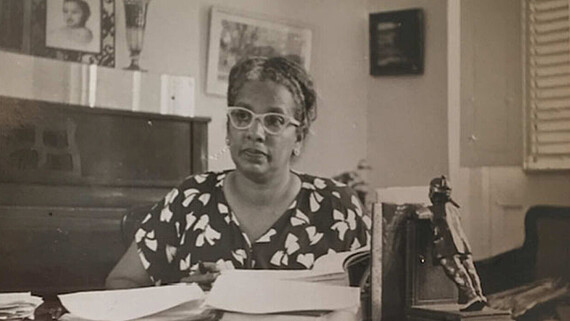

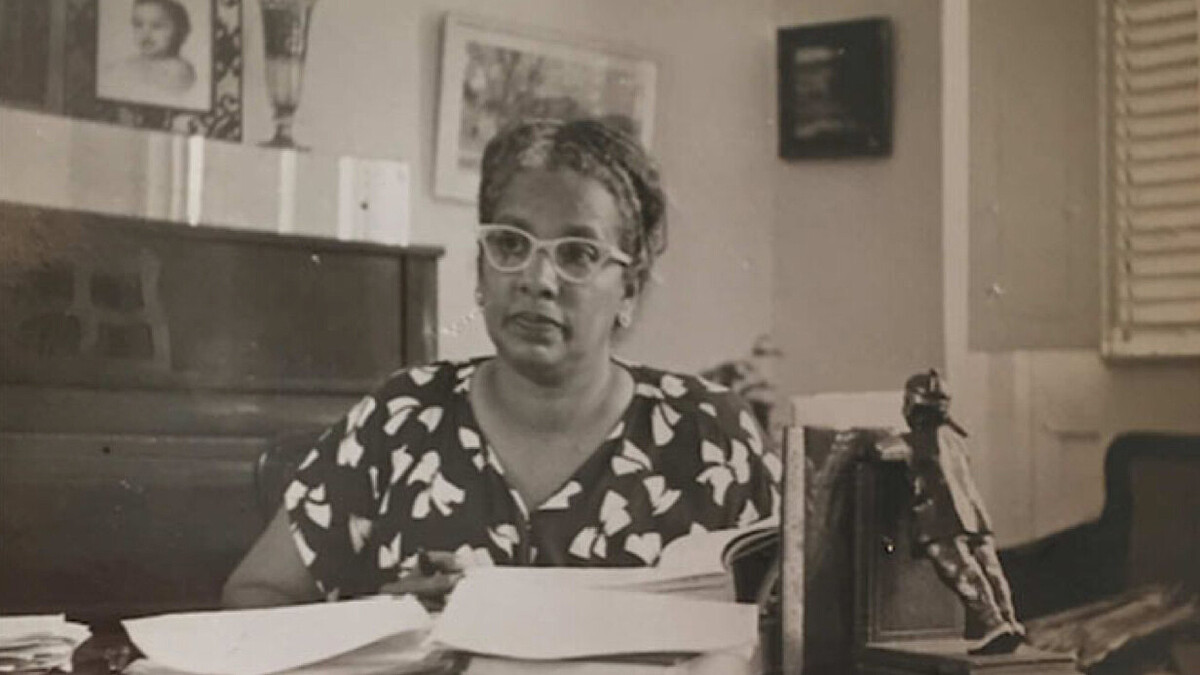

Ana Echegoyen de Cañizares (1901–1970) was a Cuban educator and activist known for her advocacy for women’s rights and her contributions to Cuban intellectual and cultural life. As the first Black female professor at the University of Havana, she played a significant role in early 20th-century movements promoting gender and racial equality in Cuba. Echegoyen was deeply involved in various organizations and lead a major alphabetization campaign in the 1950s. In this episode, we will introduce you to this exceptional figure, reflecting upon her legacy as well as the challenges of working with archival materials in reconstructing the lives of African-descended women.

TRANSCRIPT

Introduction

Ana Echegoyen may not be a familiar name to many of you. And perhaps it surprises you to hear an unknown name in a podcast about heroines. Aren't heroines supposed to be famous? And haven't they, well, performed heroic deeds?

I can promise you, it's worth learning more about Ana Echegoyen. Let me take you to Cuba in the 1930s, specifically to the capital city, Havana. Join me to discover what makes Ana Echegoyen so special. And who knows, maybe we'll also discover why she is almost forgotten today?

Historical Context

Cuba in 1933: The dictator Gerardo Machado is overthrown. The following years are a time when new discourses become possible. There is certain hope that the ideas of equality, formulated by the Cuban national hero José Martí in the 19th century, might become reality.

The post-Machado context was an opportunity to challenge racial discourses that would condense in the 1940s Cuban constitution. Officially, racism had long been non-existent in Cuba, with the concept of "racelessness" taking its place. The Cuban anthropologist María del Rosario Díaz critically assesses this: (Audio Maria I). She says that while this was officially the case, many things hadn't changed in reality. (Audio Maria II). Even though slavery had been abolished, Black Cubans didn't have the same living conditions as the rest of the Cuban population. This had, for example, an impact on literacy rates and employment opportunities. Maria del Rosario Díaz argues that despite being freed from slavery, true freedom was still elusive for Black Cubans.

In this society, we meet Ana Echegoyen. She is very well-connected in Havana's urban society. For example, she is a good friend of the well-known anthropologist Fernando Ortiz. Echegoyen was born in 1901, not in Havana, but in a small village outside the city. She came to the capital to begin her studies in education at the Universidad de La Habana. Maria del Rosario Díaz tells us that it was unusual for a Black woman to study at a university: (Audio Maria III). She emphasizes that this was only possible for women who were exceptionally talented or well-connected.

And Ana Echegoyen was indeed exceptional. Her file is still in the archives of the University of Havana, and there are notes proving that she was exempted from paying her tuition fees several times due to her above-average academic achievements.

Digression: Archival Work and Its Limits

Speaking of archives: It is truly fascinating how much knowledge is stored in the archives of this world and how many undiscovered stories still slumber in long-forgotten files. When you enter such an archive and see the old papers in completely overstuffed folders, tightly packed on the shelves, you might initially get the impression that everything is preserved there and that the archive can provide answers to all our questions if we just search long enough.

But this impression is, of course, deceptive. Not everything that is important can be found in the archive. On the contrary, we actually find only a fraction there. And behind this stand powerful structures of knowledge production. Have you ever thought about which people have material that can be archived at all? And how many aspects of a life are never recorded?

There is an entire scientific field on this topic: critical archival studies. As an academic field and profession, critical archival studies broadens the field's scope beyond an inward, practice-centered orientation and builds a critical stance regarding the role of archives in the production of knowledge and different types of narratives, as well as identity construction. It's useful to keep this in mind when exploring the lives of Black women such as Ana Echegoyen.

About Ana Echegoyen

Let’s return to our heroine. As we have already learned, Ana Echegoyen went to Havana in the early 1920s to study education. She then earned her doctorate and eventually became the chair of methodological pedagogy at the Universidad de La Habana. Ana Echegoyen was the first Black woman in the position of Chair at this University. We have already learned that, although there was officially no racism in Cuba, the reality often looked different for members of the Black population. It was quite unusual for a Black woman, especially one born in poor conditions outside the metropolis, to achieve such a high professional position. Ana Echegoyen's success can be attributed to many factors. Besides her excellent academic performance, she managed to build a strong network in Havana and gain access to the exclusive clubs of the Black elite through her contacts.

But the fact that her professional success was in the field of education was not coincidental. Education falls within the traditional understanding of female roles. This means that it was a professional field stereotypically attributed to women. Compared to other professional fields, it was more likely for women to pursue a career in education, as their work in this field was generally recognized. Professor Echegoyens activities in this area were understood as an extension of the educational responsibility attributed to her as a woman. She used this strategically to bring public attention to social issues that were important to her.

Education as an Instrument for Democratic Reform

But it was not only her involvement in education, which she used strategically. Time was also crucial. The 1930s in Cuba were a time of upheaval. You probably know about the Cuban Revolution of 1959. The images of the revolutionaries around the Castro brothers and Che Guevara went around the world and are still famous today. But some historians refer to the 1930s as a time of Democratic Revolution. A small Cuban revolution, so to speak. As we have already heard, the dictator Gerardo Machado was overthrown in September 1933. This opened a window for new discourses within Cuban civil society and politics. Old racist discourses were challenged and renegotiated: La discriminación por motivo de raza, color de la piel, sexo, origen nacional, creencias religiosas y cualquier otra lesiva a la dignidad humana está proscrita y es sancionada por la ley. What we have just heard is Article 42 of Cuba's constitution, established in 1940. This paragraph has been newly added and prohibited any form of racial discrimination. It can be interpreted as a culmination of the discussions and social progresses of the 1930s.

As we have seen, those years were a time when much became possible, and Ana Echegoyen's engagement in civil society became effective in particular. In addition to her work at the university, Ana Echegoyen was one of the founding members of the Asociación Cultural Femenina in 1935. In its founding charter, the Asociación defines its main objective as promoting the civic, cultural, social and economic empowerment of women. It emphasizes that this aim includes all Cuban women and is intended to strengthen their connection with each other. By underlining that the work is aimed at all women, it can be concluded that the role of Black women in particular should be improved, as they often continued to be marginalized. Also, because the founding members were mainly Black women, we can assume that this group aimed to bring their concerns into society and advocate for their interests. The Asociación Cultural Femenina envisioned Cuba from a Black female point of view, focused in supporting Black women. Therefore, regular social events were organized, often combined with an educational aspect. For example, there were conferences, as well as concerts, theater shows and educational excursions. Of particular importance were the night classes offered by the Asociación to enable further education and support less educated social classes. This offer was primarily aimed at women who were either responsible for childcare during the day or were in low-paid employment. This applied above average to Black women. While in white families the husband or father was usually responsible for the financial care of the whole family, the situation was different for Black Cubans. In the 1920s, almost three quarters of working women were Black.

By establishing these night schools and other educational formats, the members of the Asociación were addressing a very specific social problem: the high illiteracy rate. In an internal document from the year 1953, they describe the aim of the Asociacion as follows: Todas sabemos que una de nuestras principales tareas, es combatir la ignorancia de las masas populares y erradicar la lacra del analfabetismo. Or in English: We all know that one of our main tasks is to fight the ignorance of the popular masses and eliminate the curse of illiteracy. Those illiteracy rates were also mentioned by María del Rosario Díaz before. At the turn of the century, there were significant differences in the literacy rates of the Cuban population. At the beginning of the 20th century, over half of the white population could read and write, while only about 28 percent of Black Cubans could. Twenty years later, about 50 percent of the Black population was literate, while it was 63 percent among the white population. Even though the differences were becoming smaller, the path to equality and equal opportunities for all was still long. Ana Echegoyen's work addressed this issue. The members of the Asociación Cultural Femenina saw their work in this area as support for the democratic principles of the Cuban Republic. By helping to improve the situation of underprivileged women, they were able to increase their conditions for active participation in social life.

By the way, it is worth noting how the Asociación Cultural Femenina differed in its self-perception from many other asociaciones and clubs of the time. These were often directed at wealthy women from privileged classes. The range of the Asociación Cultural Femenina's target group was much broader and its members obviously considered the question of social class to be crucial. The variety of activities addressed women from all social backgrounds. The concerts and theater evenings were probably aimed at privileged women, while the night classes were directed at marginalized women.

Summary of Findings

After everything we've heard, we can conclude that Ana Echegoyen operated within a complex field full of tensions and contradictions. It was unusual for a Black woman to be so successful at the university and to have such influence in urban society. Officially, there was no racism in Cuba, making it difficult to name existing inequalities. Echegoyen created opportunities for herself and others by adopting a traditional female role. By emphasizing the responsibilities ascribed to her as a woman, she was able to achieve great success in the field of education. She became an intellectual authority, and in this role she was able to publicly advocate for racial equality. Improved educational opportunities for all segments of society were an important tool for her to overcome poverty. She was also convinced that a strong school system was a factor in building a strong democracy. With her work as a professor at the university and her involvement in the Asociación Cultural Femenina, she was able to actively fight against the high illiteracy rates, especially among Black women. This enabled her to make an important contribution to equality and social justice in Cuban society.

By the way, alphabetization was a topic that continued to shape Professor Echegoyen's life long after the 1930s. In the 1940s and early 1950s, she was author of a number of textbooks aimed in particular towards adults who were meant to learn to become literate through self-study. She then even led a broad-based literacy campaign in Cuba in 1956 and 1957. And from 1957, Echegoyen took on tasks in the field of literacy at UNESCO and became director of the school forum for the UN.

Outlook

We have learned what an impressive woman Ana Echegoyen was and how passionately she advocated for better educational opportunities for the Black population. A true heroine, right? The question remains as to why almost no one knows Ana Echegoyen today. One reason may surely be that literacy was also an important issue in the Cuban revolution of 1959. One of the revolutionaries' declared goals was a comprehensive educational offensive. Laws were passed to guarantee improved educational conditions. For example, Article 479 of the Ley del Servicio Medico Social states that schoolbooks for all age groups should be subsidized, and Article 561 provides for the creation of numerous new positions for teachers and classrooms.

Many people associate the progress in the Cuban education system primarily with the period from 1959 onwards, while earlier achievements and dedication of people like Ana Echegoyen are forgotten.

Perhaps this serves as a reminder to think again about who writes history and whom we collectively remember. The stories and achievements of Black women in particular are still often overlooked. But I hope the insights into Professor Ana Echegoyen's work have shown you as an example how influential people were, who we hardly remember today, but whose stories are absolutely worth knowing.

REFERENCES

Archival Sources:

- Archivo Nacional de Cuba, Registro de Asociaciones: Asociación Cultural Femenina

- Archivo Central de la Universidad de La Habana, Secretaria General: Expediente de Ana Fermina de la Caridad Echegoyen y Montalvo

Published Sources and Literature:

- Brunson, Takkara. Black Women, Citizenship, and the Making of Modern Cuba. Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2021.

- Caswell, Michelle et al. Critical Archival Studies. An Introduction, Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies, 1(2), 2, 2017.

- Constitución de la República de Cuba. Art. 42. 10 of October 1940 (Cuba).

- EcuRed, 2024. Revolución educacional en Cuba. https://www.ecured.cu/Revolución_educacional_en_Cuba

- Hernández de Cervantes, Calixta (Febrero de 1938). Mujeres ejemplares: Ana Etchegoyen. Revista Adelante, p. 13.

- Oliva, M. E.. “Queremos nuestra emancipación y la conseguiremos”: Mujeres en la prensa negra/afro de Cuba y Uruguay durante la primera mitad del siglo XX. Perspectivas Afro, 1(1), 2021, pp. 83–109.

- Pentón Herrera, Luis Javier. La Dra. Ana Echegoyen de Cañizares: Líder de la campaña alfabetizadora de 1956 en Cuba. The Latin Americanist 62(2), 2018, pp. 261–278.

- Ramírez Chicharro, Manuel. Por el bienestar de los demás. Feminismo, educación y

- asistencialismo en México y Cuba, 1934-1946. Estudios de Historia Moderna y Contemporánea de México, n. 62, 2021, pp. 183–213.

- Ramírez Chicharro, Manuel. El activismo social y político de las mujeres durante la

- República de Cuba (1902-1959). Revista Eletrónica da ANPHLAC, 20, 2016, pp. 141–172.

- Salinas Carvacho, Valentina. El pensamiento social de las mujeres negras a través de la revista Adelante (1935-1939), Universum 33 (2), 2018, pp. 193–213.

- Stoner, K. Lynn. De la casa a la calle. El movimiento cubano de la mujer en favor de la

- reforma legal (1898-1940). 1992, Editorial Colibrí.

- Vásquez, Jorge Daniel. Adelante: Blackness and Anti-Racism in Cuba. Revolutionary Papers, 12. Oct. 2022. https://revolutionarypapers.org/teaching-tool/adelante-blackness-and-anti-racism-in-cuba/

Sounds:

- Salsa loop intro 110 bpm.wav2 by oymaldonado -- https://freesound.org/s/252624/ -- License: Attribution 4.0

- Additional Sounds created via Convertio.